Image

Note: This is the first in a two-part series about 914 Sound Studios and Bruce Springsteen's early Columbia recordings. Next week: Brooks Arthur, who ran the studio, reminisces about Springsteen's breakthrough sessions at 914.)

Vini Lopez was working at a boatyard down the Jersey Shore in 1972 when he got a call from his erstwhile bandmate, Bruce Springsteen.

“He goes, ‘Hey Vin, I got a record contract. You wanna make a record?’ “ Lopez recalled years later.

Days later, Lopez — nicknamed Mad Dog — was behind the drum kit at 914 Sound Studios in Blauvelt, N.Y., for the sessions on what would become Springsteen’s first album on Columbia Records, Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J.

The studio off Route 303 would become a home away from home for Springsteen, who also recorded The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle and the iconic title track from Born to Run in that unassuming building.

The marathon recording sessions left no time to drive home to Jersey, Lopez said during a 2016 ceremony celebrating the recording studio’s legacy. “Certain times we’d be here, I swear to God, thirty-six hours straight, we’d be here. I had this giant tent and Clarence and I set it up in the back over there,” he said, referring to the band’s sax player Clarence Clemons.

It’s hard to imagine any of the musicians on those first recordings could’ve had an inkling that Springsteen would one day sell his entire music catalog to Sony Music Entertainment for an eye-popping $550 million.

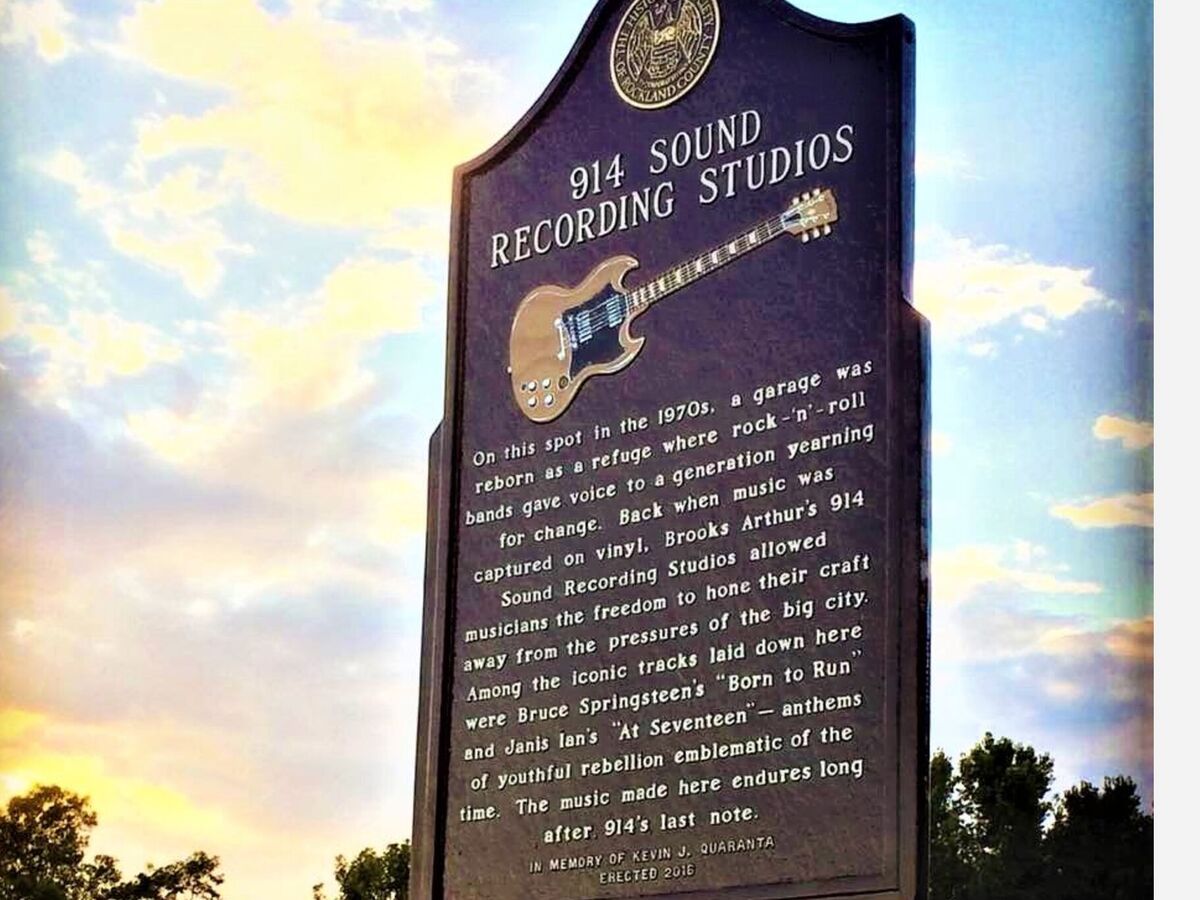

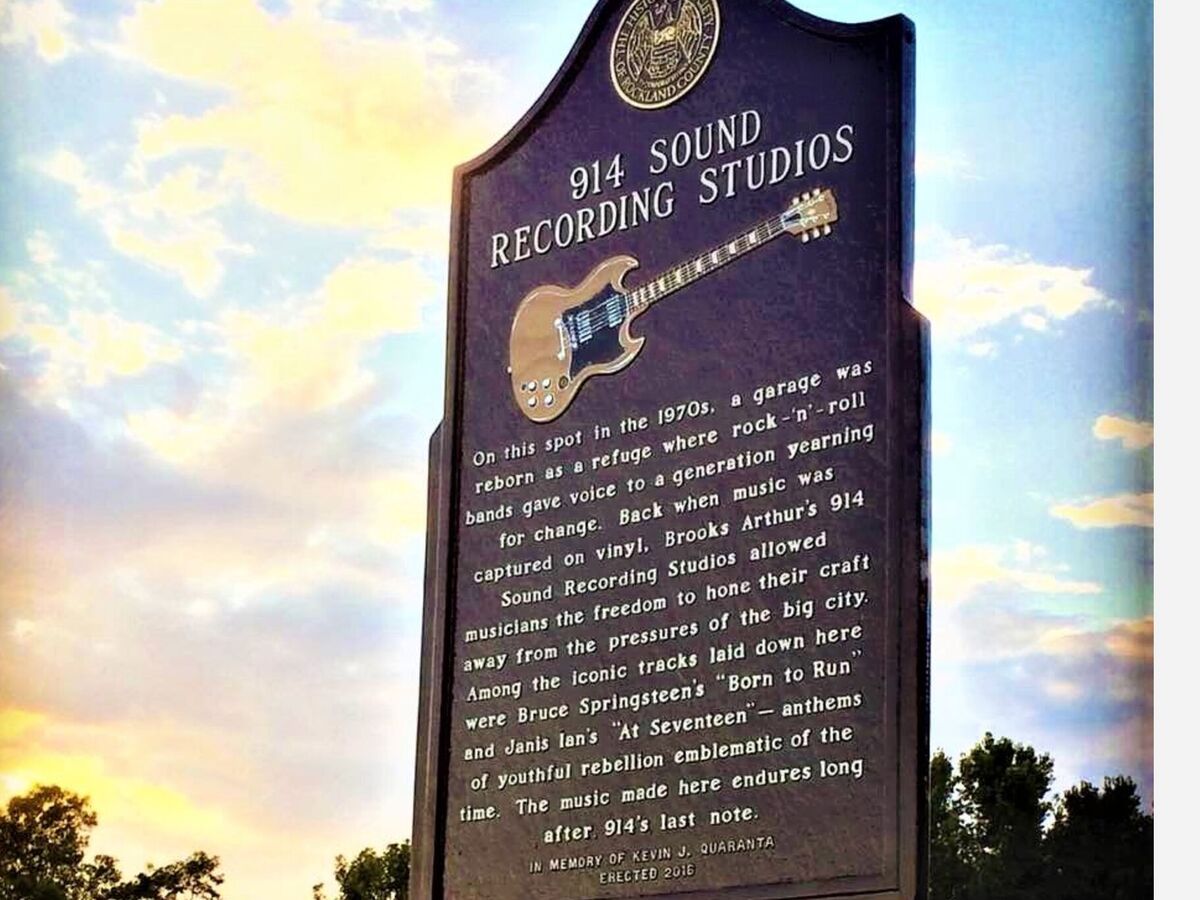

914 Sound Studios — named for Rockland’s area code at the time — was run by Brooks Arthur, who opened its doors in 1971 after engineering hit records for Carole King, Leiber and Stoller, Van Morrison and the Shangri-Las, including "Leader of the Pack" and "Walking in the Sand."

The studio in an abandoned garage had staked out a reputation for creating a laid-back vibe where artists like Janis Ian, Dusty Springfield, Blood Sweat and Tears, the Ramones and James Taylor could hone their sound away from the New York City rat race.

In his autobiography, Born to Run, Springsteen described 914 as a place where “we could get a cheap recording rate; carry on as we pleased out of site of the nosy record company bigwigs who might be too curious about how their money was being spent; and eat at the Greek diner, where I found for a muse a waitress who had the finest body I’d seen since my Aunt Betty. It was all good.”

That diner — which operated for many years as the Blauvelt Coach — had most recently become a sushi and barbecue joint before closing earlier this year. The building that once housed the music studios is now home to a car wash.

Greetings was completed in three weeks, after Springsteen convinced his manager, Mike Appel, to let him bring in other musicians rather than stick with the folk singer-songwriter format that was dominating the pop world. He called the songs “twisted autobiographies” with the names changed “to protect the guilty.”

Although the initial lineup included songs like Growing Up, Columbia Records honcho Clive Davis threw it back in Springsteen’s lap, telling him the record had no hits and would never get airplay. Springsteen answered with Spirits in the Night and Blinded by the Light, arguably the best-known tracks on the record.

The Wild, the Innocent was the next step in realizing the sound he’d come to be known for, stretching out the E Street Band on show-stoppers like Kitty’s Back and Rosalita (which Springsteen called “my musical autobiography - a preview for Born to Run.”)

While the artistic results were more satisfying, Columbia did next to nothing to promote the second album, deeming the songs too long to make it onto the radio.

After releasing two records in 1973 that were critically successful but failed to attract a wide audience or generate sales, Springsteen set out “to make a world-shaking mighty noise … to craft a record that sounded like the last record on Earth.”

Born to Run was conceived the following year, with Springsteen drawing upon Phil Spector’s “wall of sound,” Duane Eddy’s guitar twang and the “strange underbelly” of Roy Orbison’s music.

The title track took him six months to write, and during the recording sessions he wrote about struggling to boil down “seventy two tracks of rock’n’roll overkill on the sixteen available tracks at 914” — while musicians arriving for the next session pounded on the door trying to get into the studio.

Coaxing the rattling guitar sound from his Fender Telecaster for Born to Run’s solo wasn’t easy. He tried moving the amp around the studio, putting it in the bathroom, dragging it out into the backyard until he got the feeling he was after, said Larry Alexander, who was the assistant engineer on all the Springsteen recordings at 914.

A "mini-orchestra" – including a glockenspiel – was brought in to capture the sound Springsteen was looking for, Appel said.

Springsteen writes that in the end they captured the take “that had that 747-engine-in-your-living-room rumble.”

Appel leaked an early recording of the four-and-a-half minute song to radio stations and the overwhelming response from listeners was enough to persuade the record company to believe in this new artist.

That would be the only track recorded at 914 to make it onto the album. After struggling to record Jungleland, Springsteen complained the studio’s aging equipment was not capable of bringing his “last-chance ‘masterpiece’ “ home.

Brooks Arthur had already left 914 for Los Angeles, and the studio he had nurtured was in decline.

Jon Landau, the rock critic and Springsteen confidant who would later become his manager, convinced him he deserved “a first-class recording studio,” so the remainder of Born to Run’s tracks were recorded at The Record Plant in Manhattan. The album came out Aug. 25, 1975.

The record moguls wanted Springsteen to re-record the title track in a New York City studio to add more vocal, but it didn’t take long for him to realize that was an impossible task.

“We would never corral that sound again,” he writes in his autobiography. “We couldn’t couldn’t even come close to the musical integration, the raging wall of guitars, keys and drums.”

So the classic version cut in Blauvelt survived — the last testament to Springsteen’s highway run at 914 Sound Studios.